This month’s invitation is from Joe Fleming, who invites the blogging community to write about how we troubleshoot problems.

Every issue has layers.

So whenever a problem surfaces, my first assumption is that it’s part of something else. This may sound a little vague, so let me elaborate.

Whenever code throws an error, and it’s more than “you’ve missed a comma in your list of selected columns”, there’s usually more at play than just that error.

As an example, last week I joined a few coworkers in analysing a webservice that refused to play along nicely. It threw a 403 error (You shall not pass), which was technically correct, and we could fix that. After fixing that issue, we got a 500 error (I will not work). The problem is that a 500 error is a very generic error. It occurs as a last resort, when other errors can’t be handled.

This meant going further into logging of the Azure web app and finding that it was throwing a PowerShell error. Something that’s not easy to fix on a Linux container that hosts the web app. However, this was the last resort error; there were a few more errors preceding it. The first one was that it was missing a variable.

This process needs to continue, as we ran out of time, and the missing variable wasn’t the solution to bring us over the finish line.

Every issue has context.

When you release software into the world or the cloud, it is tested to the core. Right? Well, maybe not always. However, whenever an error occurs, there is always some sort of context surrounding it. Context can be the version of the operating system, the type of input, the version of supporting libraries and even the item between the backrest and keyboard.

Solving an issue

These starting points significantly impact the way I approach and tackle an issue.

Step 1: Get the details

The first thing I usually do is try and get as many details as I can about the issue. Error messages, run times, and other processes. Whatever is relevant at that time.

Step 2: Zoom out

Next, I try to zoom out as much as I can. What is the context? As mentioned, versions, editions, other processes, source systems, inputs (or lack thereof), and required outputs.

Step 3: Filter

This is the really tricky part: filter out the information you don’t need. Don’t throw it away; it may be useful later on. Try to filter out what doesn’t look like it belongs to the issue you’re trying to fix. Don’t be surprised, though, that other unseen problems arise from your work.

This is also the hardest part of issue fixing, as it requires knowledge of the code, solution, resource, or item. And yes, it’s easier to fix when you’ve built it than if you’re only supporting it. At this point, documentation is gold! If you’ve built it yourself, you can refer to it and check why you’ve made a certain choice. If you’re in a support department, you can challenge the builder why they made a certain choice.

Step 4: fixing

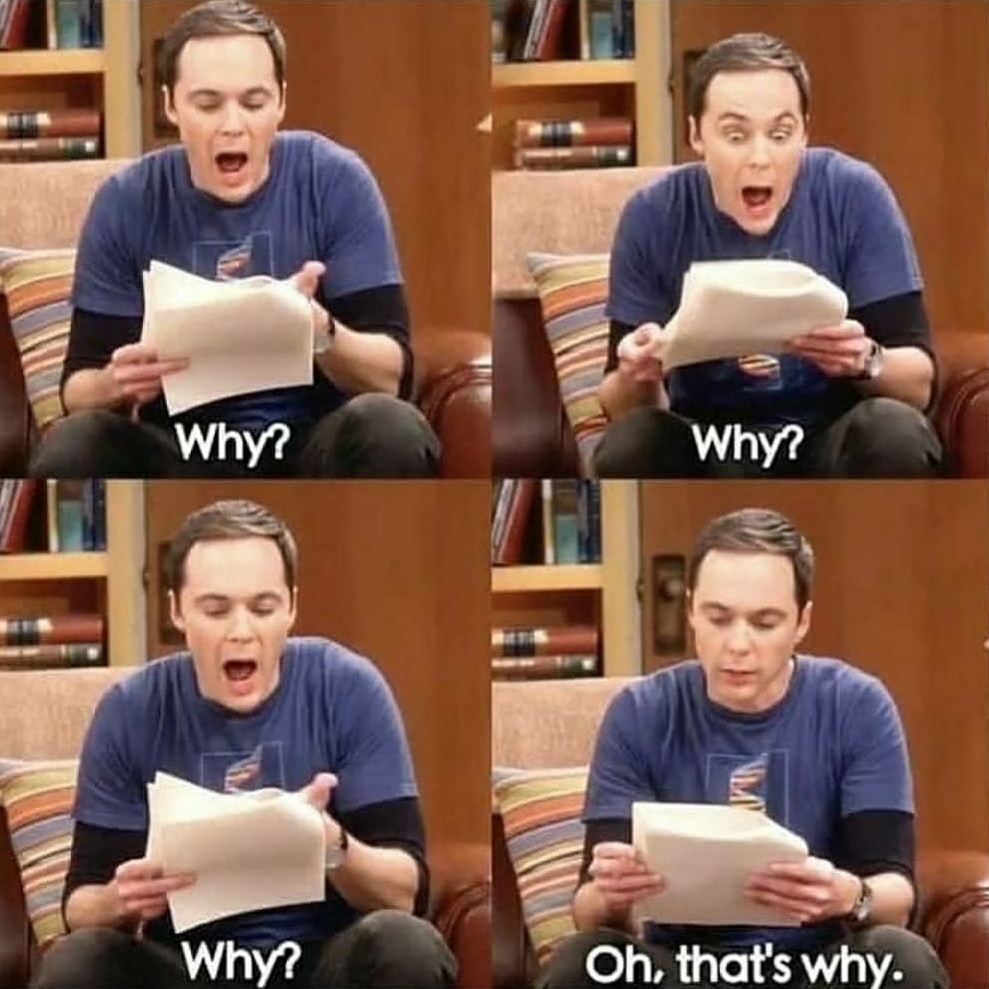

This is not a single step; it is usually an iterative process of trying things out, checking the results and moving back to step 1. In rare cases, I’m lucky and fix things on the first try, but in most cases, it takes at least three attempts to get a working fix. And sometimes it’s a temporary one.

The best way?

No, there is no best way, only your way. My approach to work aligns with the way my brain functions. If it helps you, great! If not, consider reading the other contributions on this topic, and I hope you’ll find inspiration there.

Don’t forget, the best problem-solving comes with experience. So don’t be afraid to go out and just try your hand at fixing a problem. If you fail, don’t feel bad about it. You’ve just learned a way that doesn’t work.

One thought on “T-SQL Tuesday #187: How do you solve problems”