This blog can also be known as ‘The Sequel’, not to be confused with SQL, even though Fabric SQL will be mentioned in this blog. Anyway, I digress and don’t call me Shirley.

For those of you who have been following this blog for a long time, you may have read the posts on Fabric where I’m comparing the F64 Trial with the F2, and other shenanigans. Because Fabric keeps evolving, and new releases keep coming that improve or change the behaviour, I felt it was only fair to give Fabric a new run for its capacities.

The idea is not to create a solution that works as quickly as possible. It’s not the goal to tune Fabric, nor to get the most excitement for your Euro. The main goal of this blog (and the session that I’m presenting on this topic), is to show you the differences, the error messages and where to look when you get lost. Because, for all its intents and purposes, error handling is still tricky, and it seems to be very hard to get rid of “Something went wrong” messages.

Setup

As in previous runs, I’ve been using about 500 GB of TPC-H data. CSV files with different sizes that will, at some point, either throw errors or just take ages to get processed.

For my testing, I’m using the F64 Trial, which will kick off a pipeline with many stages. Using pipelines, notebooks, Eventstreams and Dataflows Gen2 (old and new ones) to ingest data into Fabric Lakehouses, Warehouses, Eventhouses and Fabric SQL Database.

No matter how you look at it, ingesting these data volumes will hurt. The funny thing is, Fabric will show you the pain in different ways and sometimes takes quite some time to show it.

Storage

For all these experiments, I’m using Lakehouse, Warehouse, Eventhouse and Fabric SQL Database as ‘endpoints’. They all have differences that I’d like to quickly touch on, just to make sure we’re on the same level. Feel free to skip ahead if you’re confident in your knowledge.

Lakehouse

The Lakehouse uses Spark-based storage, leveraging Parquet files with Delta enabled. It will leverage the setup of OneLake easily, as it seems to be built around this. It also feels like this is as close as Microsoft can come to Databricks.

Warehouse

The Warehouse also stores its files in Parquet, but it has a SQL ‘shell’ around it. This means you can use most of the T-SQL you’re used to and apply it to your data solution. You can write stored procedures and regular SQL queries, making the transition from a current SQL-based solution easy. Until you run into the Warehouse’s limitations. Limitations mainly caused by the limitations of parquet files and the Spark engine.

Eventhouse

The Eventhouse is a whole different beast. Data is stored in a Kusto database, which is essentially a time-series database. This makes it an excellent storage for time-based data, such as IoT device data. The performance is really good, and when you learn Kusto Query Language (KQL), you’ll find that it’s not that different to SQL, and that it’s very logical. Some people even prefer it over T-SQL because you control, on each line, how much data is being processed. And if you really want to, you can also use T-SQL to query the data.

Fabric SQL Database

Finally, Fabric SQL Database, an Azure Serverless SQL Database made available inside of Fabric. Next to 0 configuration (apart from the name), and it’s there. In all honesty, coming from a DBA background, this still makes me nervous. Even though deployment is very fast, I have so little control over the database. Things like collations, backups, integrity checks, and degree of parallelism, to name just a few. Even the number of cores is unknown.

Ingestion methods

To get data from its CSV state into something Fabric can digest, I have to use the tools available to me inside of Fabric. Yes, I could store the CSV as such in OneLake and process from there, but where’s the fun in that?

Pipelines

Pipelines and the copy data activity are one of the easiest ways to do this. Tell it where the source is, where to write it, and done. Well, almost, because you have to tell it what the schema of the file is. And, because my files are built differently, the separator isn’t a comma but a pipe sign. But with that, you’re good to go. The copy data will read the CSV and mash the results into one of the available storage options.

Notebooks

Using a notebook is a little bit trickier as it’s not unusual to see that clients and third parties restrict access to their data by either using IP filtering or requiring some sort of VPN. Both of which were not supported by Notebooks, though Microsoft just released something in preview that is heading into a new direction for Notebooks and connections.

As I did not wish to open up my storage account to the world, I had to put my files in OneLake, using a different capacity to power the Lakehouse, and process from there. As an added complexity, Notebooks can use environments where you can do much of the configuration yourself. To prevent an endless number of variations, I limited myself to the default, the Native Execution Engine and the preview Fabric Runtime 2.0.

Dataflow Gen2

When I started testing in Fabric, I quickly came to dislike the Dataflow Gen2. Not only slow, but it’s also weird to configure (I’m most certainly not coming from a Power BI background!) and extremely costly. Some time after testing, Microsoft released the Fast Copy option that alleviated some of the pain. At FabCon Vienna in 2025, there was a major announcement on the Dataflow Gen2 CI/CD. Long story short, this new version works much more efficiently, uses less capacity, but is still, for a code person like me, weird to work with. Putting that last argument aside, I think it’s a very viable option if you need to go low-code.

Eventstream

The last option used is the event stream. In a project, we’re processing an incoming stream of XML data into structured data. I used this knowledge to build a setup that allows me to read from an Azure storage account and write the data to an Eventhouse. What you need to be aware of is that my CSV is malformed, so only the RAW option works. And there is another limitation I ran into, more on that later

Different tests

One more paragraph before moving to the results. And that is the difference between running everything serial (which means the region file/table first, then nation, then parts, etc.), opposed to running everything in parallel (meaning all the ingestion processes for the specific ingestion method and target are started at once). My main questions were, does it matter in time used, does it matter in capacity used, and are there differences in errors?

Time for action!

Pipeline, serial ingestion

Welcome to the party, pal! The action starts with loading the data using pipelines and slamming it into the Lakehouse, Warehouse and SQL database.

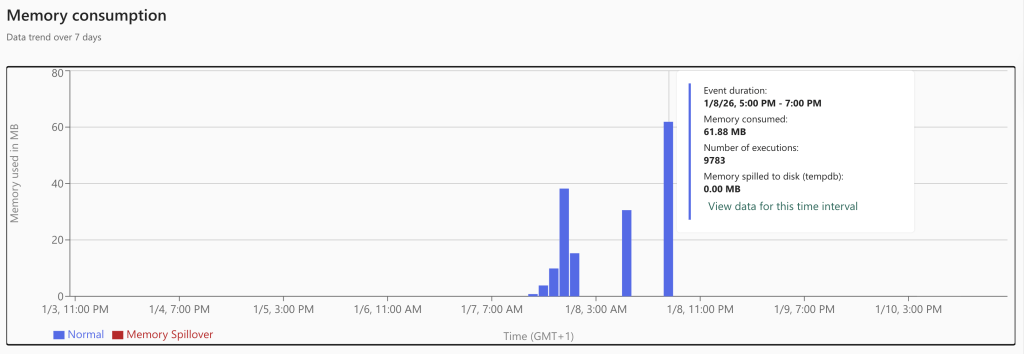

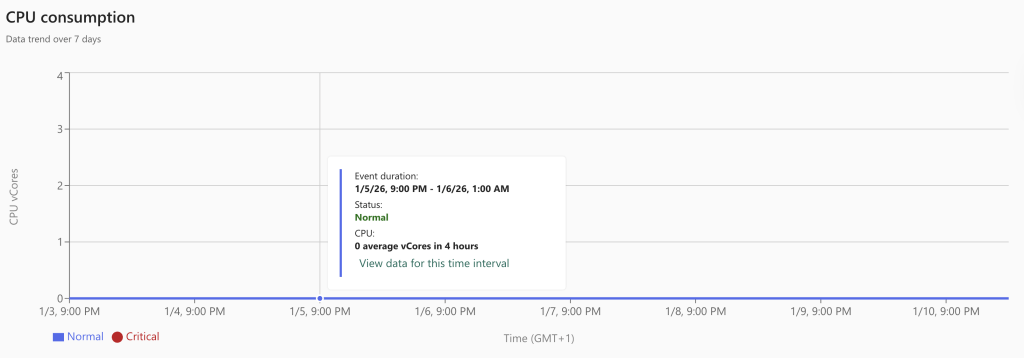

As expected, the Lakehouse just works. It’s not very lightweight, but the data is transferred and transformed from CSV to parquet without many issues. To my pleasant surprise, the Warehouse wasn’t really angry with me either. Yes, it was a bit slower and took some more capacity units, but all in all, it worked. And performance-wise, it’s not that far from the Lakehouse. Something unexpected was the delay with the Fabric SQL database. To me, it seems it was somewhat surprised by the incoming data load and had to do quite a bit of extra work to store it.

My (somewhat educated) guess is that, since it’s running in full recovery mode, every transaction is fully logged. Lake and Warehouses do not suffer from this. Also, data is automatically replicated from the SQL Database files (MDF, NDF, and LDF) to OneLake. This won’t help performance either. Finally, I’m wondering how many CPUs the database was using; the monitor shows exactly 0, even though there were quite a few processes running.

Pipeline, parallel ingestion

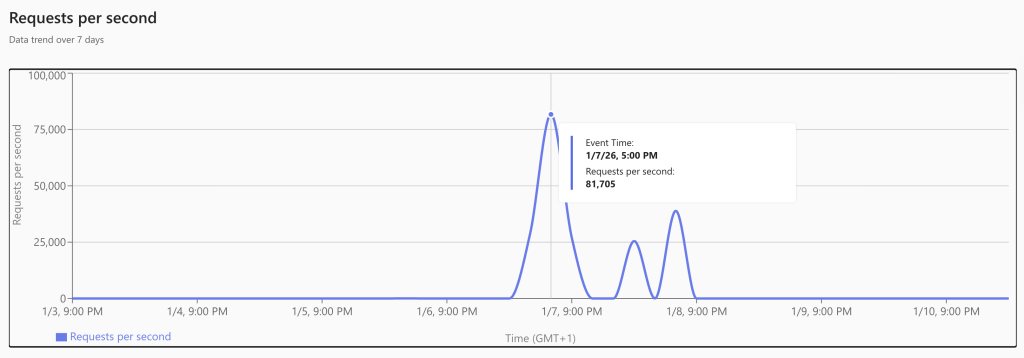

Part two of the tests involves removing the lines between the tables. In other words, I’m feeding the pipeline 500 GB of data and just letting it rip through it.

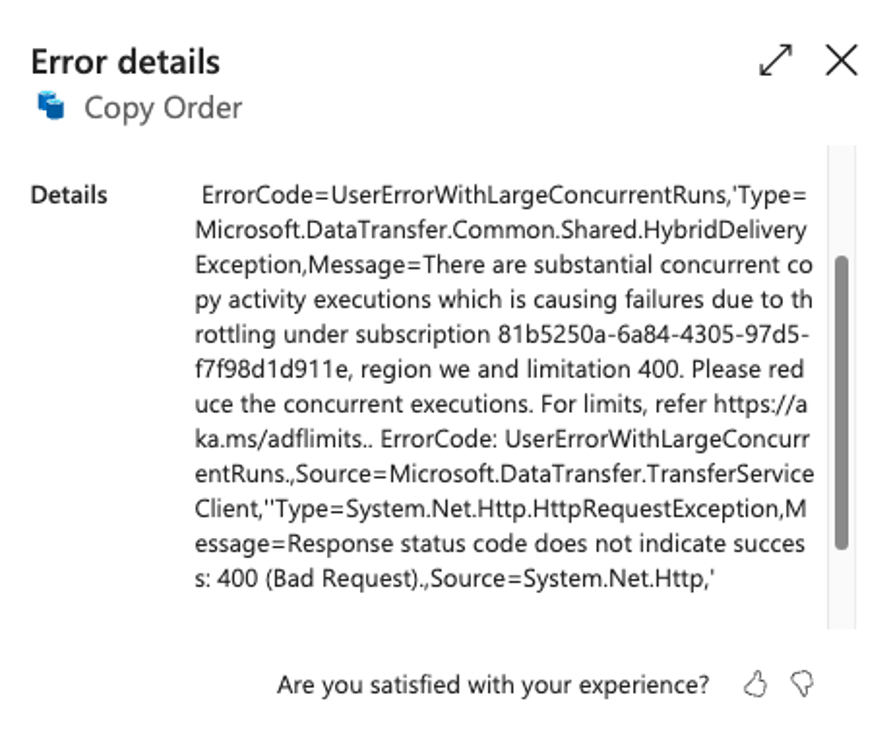

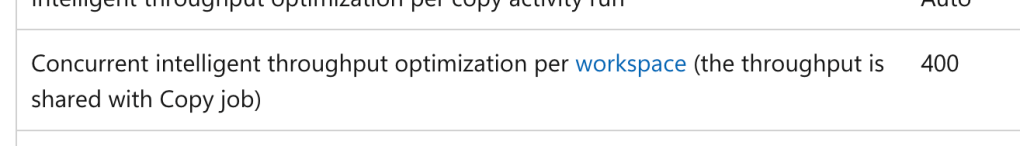

The Lakehouse target, again, gets the job done. Both Warehouse and SQL Database fail, but with a weird error. I’m hitting a limit of 400 somethings.

I think it has to do with data transaction units, but the math doesn’t hold up, especially when you look at the documentation, mentioned in the link.

This is the calculation I’ve made:

| Table name | Used Data Integration Units | Running total |

| Nation | 4 | 4 |

| Order | 256 | 260 |

| Part | 44 | 304 |

| Supplier | 4 | 308 |

| Region | 4 | 312 |

| Customer | 36 | 348 |

| LineItem | 256 | 604 |

| PartSupp | 228 | 832 |

As you can see, the last two tables, the ones that went into the error, cross the boundary of 400.

Looking at the documentation, you can see a different number. The funny thing is, when you try it dig a bit deeper, you’ll find a different link, click here to follow. There, you see wildly different numbers compared to the previous link.

An error message sending you to a wrong link, besides being not very clear about what’s actually going wrong. So always check a level deeper before accepting the error message. In a way, these are just like an AI agent; you should always check their work too.

Dataflows Gen2 to lakehouse

The next tests are using a dataflow Gen2 to load data into the Lakehouse. There are a few tricky parts here. First, going serial is a huge challenge, as this item can’t be configured to load just one table, then move on to the next; I have to create a separate flow for each table. With that, it will pick up just one file.

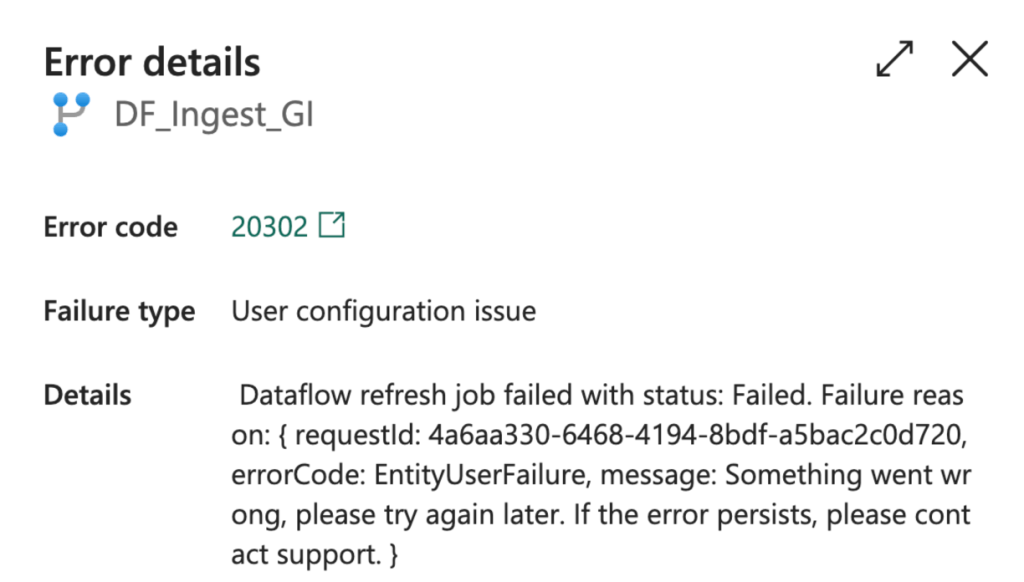

When I created the dataflows to plough through all of them, without caring about order or anything, think of it as a very parallel process, both the dataflow Gen2 and the newest one with CI/CD enabled and all the cool new features turned on, everything just failed. And my main issue with error messages came back again.

So yeah, something went wrong, but we’re not going to tell you what it was. Coming from a code-first background (T-SQL!!), I still have a bit of an issue with low-code solutions. I like to be in control and see squiggly lines when I make a mistake. I really don’t mind being wrong or doing something stupid, but just tell me. When an item fails, sure, no problem. But tell me what I did wrong, and preferably a way I might solve it.

Notebooks to Lakehouse

This is my favourite part. Not only because every architecture I design for customers relies heavily on this concept, but also because I’m still convinced it is the best way to load and process data in Fabric.

I wrote a notebook that processes the data serially, table by table. And one set of notebooks that will do the same thing, but all in parallel. The best thing is, the only failures I ran into were because of mistakes I made. Like not using the correct Lakehouse or ABFSS path. When the config was correct, the processing just worked flawlessly.

Different environments

When you’re using notebooks, you can start with the default environment or create your own. When you go into the direction of creating your own, there are almost an infinite number of possibilities you can use. As much as I love you, my dear reader, I can’t test them all. So I went for the three main options: Default, native execution engine, and the 2.0 preview.

Before I actually ran the tests, I had the feeling that the native execution engine would be the fastest, in any case, outperforming the default. Maybe the preview 2.0 version would be quick as well, but I wasn’t sure.

So here are the results, with the fastest times in bold.

| File | Default | Native Execution | Fabric 2.0 |

| Serial | 22:30 | 22:37 | 21:15 |

| region | 01:19 | 00:56 | 00:45 |

| Nation | 01:15 | 00:56 | 03:00 |

| PartSupp | 08:52 | 09:30 | 09:45 |

| Part | 13:05 | 15:16 | 07:05 |

| Supplier | 01:53 | 01:22 | 02:10 |

| Customer | 04:38 | 02:31 | 04:27 |

| Orders | 09:25 | 12:20 | 10:00 |

| LineItem | 18:50 | 14:11 | 10:57 |

Apart from the differences, I found it most surprising that they were all over the place. Fabric 2.0 has 4, the Native execution engine has 3, and the default is the quickest on two occasions. This is an average over three runs, by the way, so some outliers will influence the results. However, I think you can still see that the defaults are the least good option to work with, even though they are not bad.

Eventhouse

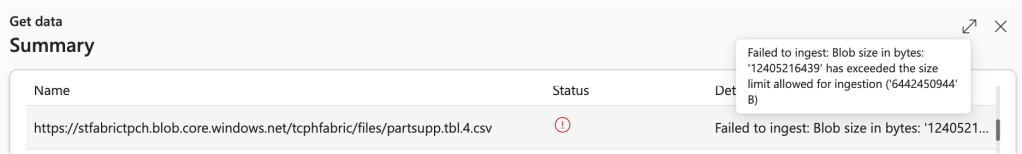

Having worked with clients in Realtime, I’ve quickly come to really like the Realtime experience in Fabric. Even though there are some pitfalls to be aware of (like the Always-On option that can eat capacity like mad), it has solid use cases and can handle incredible amounts of data without issue. If you’re working with XML that’s fairly stable and the files keep coming in, it is a very efficient way to handle them. That is, up to a point, because I ran into an issue that isn’t, as far as I know at the time of writing, clearly documented.

Apart from the fact that someone decided to show errors in Bytes (640 Kb should be enough for everyone, right ;)), it is a clear message that I’m doing something wrong. If you don’t feel like doing the math, I’ve done it for you. The message says my 11,5 GB file is larger than the allowed ingestion limit: 768 MB. Apart from the bytes part, this is an error message I can work with. In theory, I could have split all the large files into smaller ones, but that would defeat the purpose of these tests, which is to see when and where Fabric breaks.

Costs

The main point of this exercise is to find out what it all costs. Not only in capacity units, but also in money. Because in the end, we all want the most excitement for our euro. But to find out the cost, you first have to calculate this.

| F2 | F64 |

| 60 CU(s) per 30 Seconds | 1920 CU(s) per 30 Seconds |

| 60 * 2 * 60 *24 = 172.800 CU(s) per day | 1920 * 2 * 60 *24 = 5.529.600 CU(s) per day |

| Costs 272, 97 euro each month, 9 euro each day | Costs 8.734,93 euro each month, 291 euro each day |

| 1 CU = 9/172.800 = 0.00005 euro | 1 CU = 291/5.529.600 = 0.00005 euro |

| 60 CU(s) = 0,003 euro | 1920 CU(s) = 0,101 euro |

Using this number, you can calculate the actual cost of items and decide whether they’re worth it for your business needs.

Costs in terms of storage:

| Storage | CU cost | Euro’s |

| Lakehouse | 8.758 | 0,43 |

| Warehouse | 10.626 | 0,53 |

| Eventhouse | 4.105 | 0,20 |

| Fabric SQL DB | 64.715 | 3,23 |

Storage-wise, it’s clear that Fabric SQL DB is the most expensive, even though it’s not crazy expensive.

When I presented this session, an attendee asked me about the comparison between CU’s per-GB processing. Especially because the Eventhouse was very quick, but also faulted fast because of the file sizes. As shown in the table below, the Eventhouse didn’t store a large amount of data. But this is only part of the story, as Eventhouse is exceptionally good at compressing data. The original data size is almost double that of what is stored.

| Storage | Datavolume Stored | CU per GB |

| Lakehouse | 5TB | 1,75 |

| Warehouse | 595 GB | 17,85 |

| Eventhouse | 39 GB (72 GB original) | 105,2 (57 original) |

| Fabric SQL DB | 537 GB | 120,5 |

Looking at the processing costs, there’s a lot to learn.

| Type | CU cost | Euro’s |

| Pipelines | 3.778.380 | 188,91 |

| Notebooks | 169.412 | 8,47 |

| Event Streams | 4.649 | 2,32 |

| Dataflows Gen2 | 1.637.230 | 81,86 |

| Dataflows Gen2 CI/CD | 51.560 | 2,57 |

This tells a very different story. As you can see, using pipelines is very expensive. Dataflows Gen2 are costly as well, even more so given that they failed. The new ones are much less expensive, making the failure a tolerable experience. Spending about 2.5 euro’s to find out you made a mistake isn’t that bad. Notebooks still look like they are the most cost-effective option.

Tying it all together

So, after all these tests, anything to conclude?

First of all, these tests are a little silly in their setup. Slamming a huge amount of files into Fabric to see what happens isn’t exactly a production scenario. Yet this was already disclaimed at the beginning of this post. This was more about finding differences and seeing when, how, and why it breaks. But it’s also meant to be an inspiration to start testing your own workloads.

I can go on and tell you what the best solution is, but this is only part of the equation. There are other factors to consider as well. One of these is your company’s workforce. If you’re working with people who are amazing in SQL, but limited in PySpark, it makes a lot of sense to build the solution in a Warehouse. If you are on your own, coming from a Power BI background, using Dataflows Gen2 could be the way to go.

Apart from knowledge, budget to learn and expand expertise is something to factor in. This includes time. The cost of learning a new language and toolset may not outweigh the time and class costs. This is something you have to calculate for yourself.

Another thing to keep in mind is when you hire a consultancy company. I know a few, and they all have their preferences. But always make sure to ask if they can build the solution in a toolset that fits your company, expertise and workforce. It’s up to you to decide how to work with their answers.

Ok, but you want to know my preference? Well, when I started with Fabric, I took an immediate liking to Lakehouses and Notebooks. Even though I find writing notebooks frustrating (I mean, a space has a meaning??), they offer the best performance and flexibility for the lowest price. The downside is that you can’t force them to use an On-Premises Data Gateway to leverage VPN or IP filtering. In those situations, I like to revert to a Copy Job, a Copy Data activity, or a dataflow Gen2.

Finally, if you’re running workloads in Fabric, you probably want serious monitoring to see what happens. The Fabric Capacity Metrics App can help you with a lot of basics, but check out Fabric Unified Admin Monitoring (FUAM) for deeper monitoring and analysis.

One thought on “Loadtesting Microsoft Fabric, part II”